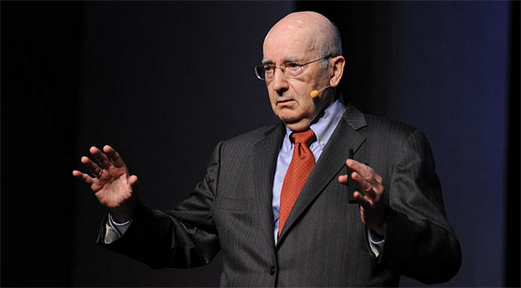

Globalization, Migration and the World Economy with Ian Goldin

| Globalization is the most powerful force influencing humanity at this time. | |

| |

| What are some of the main challenges and opportunities with globalization? |

| Globalization is the most powerful force influencing humanity at this time. It influences all aspects of our lives. I think its most important aspect is the flow of ideas across national borders, which means that we've moved to a world where there are now about five billion people sharing ideas, compared to less than one billion people only 25 years ago before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

I think the second key aspect is economic. Flows of goods, services, products and finance, so trade and also virtual trade. The movement across the Internet of commerce and supply chains is also a major aspect. Third, contraband of various types is also flowing across borders, and this is the spillover effect of globalization. If we don't manage these negative flows more effectively, this could really be globalization’s undoing, because very bad things like pandemics, cyber-attacks, financial crisis and terrorist attacks flow as well as very good things. And then the fourth dimension is migration. It has been the slowest of the globalization forces because as we've become more globalized, countries have actually put up stronger border controls, except internally within Europe. This goes against the other globalization trends. |

| I've discovered that the amount that people will have to save now is 100 times greater than what it was in the 1980s to maintain equivalent standards of living, because we live much longer, and the risk-adjusted returns are much lower. This has very significant implications for savings and investment. | |

| |

| What are some of the most important future trends you see emerging over the next 10 years? |

| The key driver of change will be demographics, with a very rapid increase in longevity at the same time as a collapse in birth rates, and it will happen all over the world. Median ages within countries will double over short periods of time, and so the elderly will increasingly dominate politics, with significant political ramifications. It also has major ramifications for savings and investment around the world. I've discovered that the amount that people will have to save now is 100 times greater than what it was in the 1980s to maintain equivalent standards of living, because we live much longer, and the risk-adjusted returns are much lower. This has very significant implications for savings and investment. For example, where do the savings come from, and where do they go? How will this add up?

The second major trend is economic. Emerging markets are growing at two to six times the pace of the old advanced economies, and the demographic drivers will change global consumption patterns dramatically. Emerging markets will account for 80% of global consumption by 2050, with Asia over 60% of this. Emerging markets already account for well over half, and that fundamentally changes who is consuming, what they are consuming and where they are consuming, and that in turn changes the major world markets for products and services. The third big global trend is fragmentation of politics. People are trying to become more local while the world has become more global. This phenomenon results in a growing tension between globalization and nationalism. So how this plays out, and whether we're able to manage these global challenges is a key question. The fourth trend is the pressure on natural resources, the unintended spillovers of our success. We will have 3.5 billion new middle class consumers over the next 20 years, so we will have a very rapid rise in carbon dioxide emissions, consumption of livestock and fish, and increasing antibiotic use. All of those things are fine when small groups of people do them, but when you have four billion people doing them, the spillover effects are much greater. I see the systemic risks arising from our successes and from our higher incomes and higher connectivity being a big new trend, what I call in my recent book on systemic risk The Butterfly Defect of globalization. |

| This is not something that can be delegated to a Chief Risk Officer and silos compound the problem of risk management. It is everyone’s responsibility to manage risk. | |

| |

| Can you give us three tips for navigating the systemic risk associated with global connectivity and technological change? |

| Yes, the first tip I would give is that it is vital to understand what these new risks are. What we've seen in the financial crisis and in other areas is that most institutions are totally unfit for the 21st century. Even the smartest institutions like the IMF didn't see the financial crisis coming. Navigating this new world requires an understanding of how it hangs together, the new nodes and networks and the new emergent risks.

The second strong emphasis I would place is on diversification strategies, because we don't know where the next shocks will come from. Diversified portfolios and strategies are very important. Where one builds one’s headquarters, how one builds supply chains or constructs financial portfolios requires an understanding of the new opportunities and risks. The third tip is developing a risk culture within organizations that starts with the chairman of the board, because everyone needs to be involved. This is not something that can be delegated to a Chief Risk Officer and silos compound the problem of risk management. It is everyone’s responsibility to manage risk. Whether a cyber-attack, a pandemic or a financial crisis, we've found that the existing systems of supervision and control are totally unfit for twenty-first century purposes. There is no big brother you can rely on out there to stop risk, so it has to be all of our responsibility to manage it. That requires a risk culture in the organization, it requires training and it requires contingency in other planning. It also requires psychological resilience. We will be hit by surprises, so the question is, are we capable of bouncing back? Are we capable of responding in a timely fashion? Answering those questions requires a great deal of thought and preparation from organizations and individuals. |

| If you look at the Noble Prize Winners, the Academy Award Winners, it is very evident that disproportionate shares of the winners are migrants. This is not an accident. | |

| |

| How will human migration shape our world? |

| My book Exceptional People is subtitled "How Migration Shaped Our World and Will Define Our Future", so I see it as the most powerful influence. Of course it’s the reason we all are where we are today. Understanding our migrant origins, short-term and long-term, is vital and so is understanding how this is the key driver of the dynamism of our economy.

If you look at where most patents come from, for example, or who is the most innovative, who is at the forefront of business and technology, in medicine, in other areas like the arts, migrants tend to outperform. If you look at the Noble Prize Winners, the Academy Award Winners, it is very evident that disproportionate shares of the winners are migrants. This is not an accident. Migrants tend to be the risk takers; they tend to be exceptional people within their own societies. This is true within the countries I go to. Not just the skilled, but also the semi-skilled and unskilled migrants. Steve Jobs wouldn't have arrived in the US if his parents had not been given permission to go there, and migrants founded all the iconic firms I can think of in Silicon Valley. So it is a vitally important area, especially in terms of future demographics. About half of the kids born in the US today will be born to migrant parents, even though they are only about 11% of the population. So one of the great sources of future strength for the US are migrants. What its government does about migrant policy is vital to its future. |

| What are some of the main economic trends that will shape our global future? |

| The main economic trend that is a source of strength for the world is the rebalancing of the global economy due to emerging markets with an increasing share. Now when the US gets a cold the rest of the world no longer gets pneumonia, and the strength of the rest of the world allows the US to recover. If the emerging markets weren't so strong, the US wouldn't be growing as strongly as it is either, and that is also true of Europe, although of course it is much weaker.

Another trend is the move to fragment and elongate supply chains. Still another is de-skilling over time, the hallowing out of working and middle class jobs through machine intelligence and automation. One of the groups in the Oxford Martin School which I am the Director of has predicted that 47% of US jobs will be lost to machine intelligence. These are key factors driving the future. |

| What other projects are you currently working on? |

| I'm the director (dean) of a very large interdisciplinary research faculty at the University of Oxford, and we are working on the frontiers of medicine and physical, life and social sciences. We have 35 different projects addressing critical, cutting-edge issues ranging from neuroscience, stem cell therapy, nano-medicine, cybersecurity and new energy forms to economics. In the area of economics we are trying to make finance more stable and to understand risk.

There is also a lot of work going on with the future of computing and automation and their impact on employment and skills. I'm involved in many of these, though as an economist I tend to look at the economic implications. I have a banking background so I often think about the impact on markets and finance, but I also look at the impacts more generally. To bring Ian Goldin to your organization, please contact Speaking.com at: Speakers@Speaking.com. |